Original air date: 31 October 1990

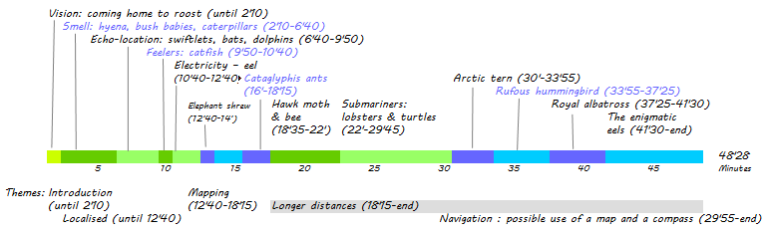

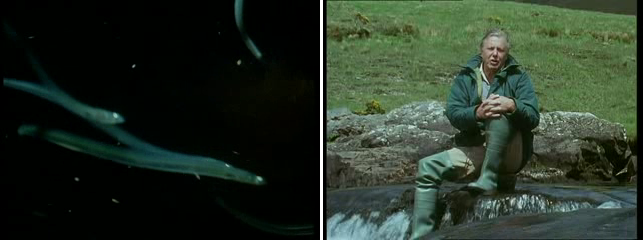

The timeline gives a detailed look at what happens in the episode. Green text indicates connecting words from Attenborough when introducing the next part. Dark green indicates that it is truncated (cutting several lines into a single one). Normal green (along with quotation marks) obviously indicates direct quotation.

The introductory words, for the episode, were perhaps a bit long to include above but they were very ‘fitting’:

“It’s the end of another African day, and the game animals are preparing for the night. Baboons are climbing up into the branches of the trees and birds are coming in to roost. All these animals rely upon their eyes to find their way around, as indeed do I. In a short while it will be totally dark. Without a torch, I would be very well advised not to try and stumble around in the darkness. But not all animals rely on sight. Others use other senses to find their way around. And in a short while, they will be venturing out”.

Selected material

Scent marking

Caterpillars leave scent marks where ever they go in search for food. They can trace back these marks on their way back and the rest of them can follow them using the say method, telling apart if there is a single mark or double.

Navigating independently from your location (15’15-18’15)

Cataglyphis ants can navigate in the sand dunes of a featureless desert. They can search for meal and when they find it they take aim of the angle to the sun and using its polarised light and go straight home. They are independent of their home ground and can venture into the unknown. Longer journeys are consequently possible.

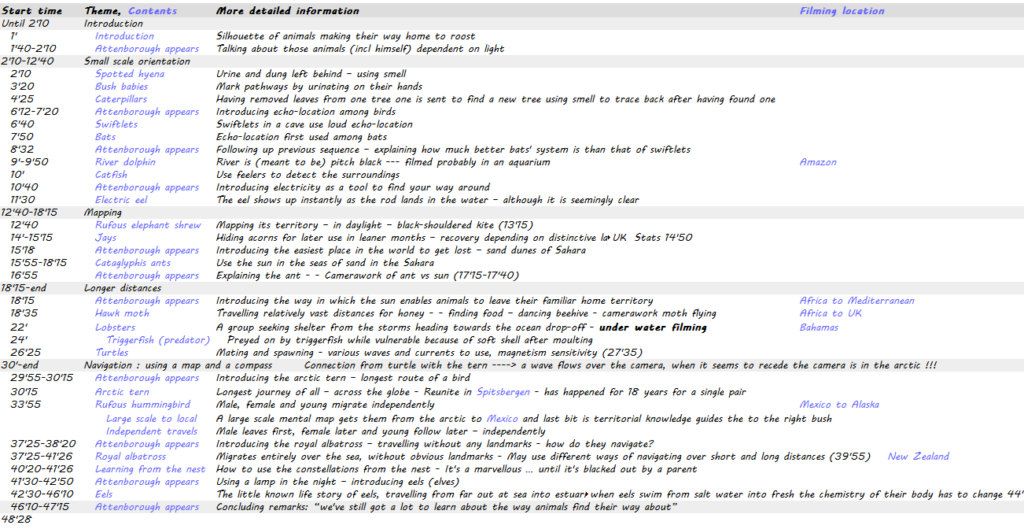

The longest migration of any animal without actually leaving the planet (30’15-34′)

The arctic tern migrates from the arctic summer to the Antarctic one to enjoy continuous sunlight around the clock. Frame on the left shows the bird, on the right emphasises the length of the journey.

The longest migration relative to body size made by any animal (34′-37′)

The birds travel eg from the Rocky Mountains to Southern Mexico (in two months) where they return to the same flowering bush every year.

These were necessary because of the complicated subject as indicated in his final words:

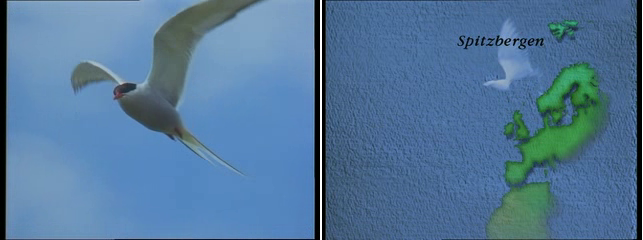

“When the adult eels swim across the continental shelf, they disappear into mystery. No one has ever caught one more than 50 miles from the coast. That may be because they swim at a depth that is far beyond the reach of any normal net, and they can’t be caught by a hook with bait on it because they don’t feed ever again. But how do they guide themselves on these astonishing journeys? Young elvers can’t be guided by their parents because they cross the Atlantic by themselves. Adults can’t guide themselves by the sun and the stars because they swim at such a depth that they can’t see the sky. Maybe they have some kind of in-built compass. Perhaps they use a sense we haven’t yet identified. We’ve still got a lot to learn about the ways in which animals find their way around.”

The mystery of eel navigation (42’30-end)

Since this series was made scientists have learnt a lot about their navigation. They seem to have an in-built compass sensing the geomagnetic field of the planet (2017).