Original air date: 19 January 1984

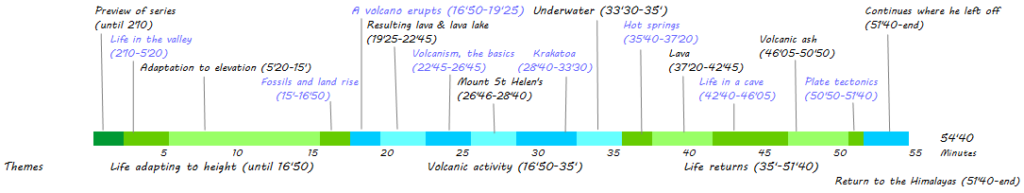

As the graphical outline below shows the episode is composed of three parts with a short stubs at either end.

As the above image shows the programme is in three parts. It starts with a short piece about how life (plants and animals) adapt to altitude and drop in warmth, something that will be treated later in the series. This is followed by the inner parts of the earth getting to the outside – consequently destroying life, and how life always returns.

A more detailed look at the episode can be seen in the text version below

The main reason life always tends to return despite dire circumstances can actually be seen in a later episode “The Sky Above“, the air is loaded with young life, like spores, that will settle as soon as the environment returns to being viable; the lava or hot spring has cooled down enough.

Selected material

Life’s adaptation to height

Attenborough wanted to start this, the first episode of the series, with an arresting three minute introduction to life’s adaptation to height.

Rhododendrons, an ordinary garden plant in UK, but here it grows wild (top left). It is being fed on by monkeys (top right) and all kinds of birds (bottom). It’s main role is not producing food for various animals, the fruit they are seeking is just a down-payment for distributing its seeds somewhere further away.

A yellow-throated marten on the foothills of the Himalayas (9’04)

Tahr

One of the animals Attenborough encountered on the foothills was the strange tahr, which turns out to be a relation to both goats and sheep (13′). They only exist in Asia.

The completed sequence did exactly as he had hoped (p.308-9). But as the detailed timeline reveals (better than the graphical one) this sequence, starting at 5’20, takes much longer (lasting until they reach the village, [13’50]). The three minutes have passed when Attenborough appears again later in the foothills. Despite this I would not sacrifice a single shot as the sequence feels very logical.

Arriving in the village and deciding to underline the importance of adaptation of humans the book mentions him panting as if struggling for breath when passed by two working women shortly after arriving at the village. This sequence has obviously been removed from the film, after complaints from viewers (p.309). Actually it seems that talking from studio he has already started preparing the viewers for this panting before switching to his onscreen voice (14’35).

When Attenborough arrives in the village he starts talking about how young this terrain actually is and explains it through the fossil record until he is interrupted with a volcanic eruption, the main part of the programme. Near the end of the programme plate tectonics are mentioned, shortly before the return to the Himalayas where Attenborough finishes (51’40) what he was talking about earlier in the programme. Although this may be a one off, a case where almost the whole programme passes from the start of a sentence (15′-16’50) to the end of it (51’40) as shown in the detailed outline, it is only a conspicuous case of how all their sequences are produced: If Attenborough doesn’t speak on screen he presumably does so afterwards from studio.

Introduction to volcanic activity

Right at the beginning of sketching the series Attenborough had decided that the first programme of the series apart from starting with a brief introduction to life’s adaptation to lowering temperatures should deal with the ‘creation’ of new land. Volcanism isn’t predictable and all the world’s volcanoes were inconveniently quiescent at that time. Even though there are constantly active volcanoes in Hawaii they do not offer any visual spectacle as is needed in the first programme of a series in order to make the undecided viewers stick with the programme instead of switching to another channel. In Hawaii the molten lava slides like a black treacle down the mountainside. What they wanted was a bit more dramatic like a fountain spurting fire into the air. Their best chance seemed to be in Iceland.

Sitting at a meeting of the Trustees of the British Museum on a Saturday morning in November 1981 having recently been appointed he was a bit unsure of himself one of the Museum’s messenger quietly walked in and handed him a note. Having read it quickly he caught the Chairman’s eye and said: “May I have permission to leave. I have to film a volcano that has just started to erupt in Iceland.” It wasn’t his first spoken contribution at such a meeting but it created the biggest impression so far. It was a race against time as no-one knows how long an eruption will last, it may be hours or weeks. He got to the airport just in time for the Reykjavik check-in. Landing in Iceland they were met by an Icelandic film crew (they did not have their regular crew with them) all of them being taken to the mountains to a guesthouse where they met the geologist who had alerted them. He told them the eruption had already lasted two days.

Enjoying strong tailwind they could get quite close to the lava fountain. Only thirty hours after leaving the meeting they had this all-important sequence.

It was a race against time as no-one knows how long an eruption will last, it may be hours or weeks. He got to the airport just in time for the Reykjavik check-in. Landing in Iceland they were met by an Icelandic film crew (they did not have their regular crew with them) all of them being taken to the mountains to a guesthouse where they met the geologist who had alerted them. He told them the eruption had already lasted two days.

Enjoying strong tailwind they could get quite close to the lava fountain. Only thirty hours after leaving the meeting they had this all-important sequence (p.299-301).

Attenborough starting his talk about volcanism in front of a volcano in Iceland (17’25) while standing a safe distance in front of an eruption in Iceland, the one mentioned above

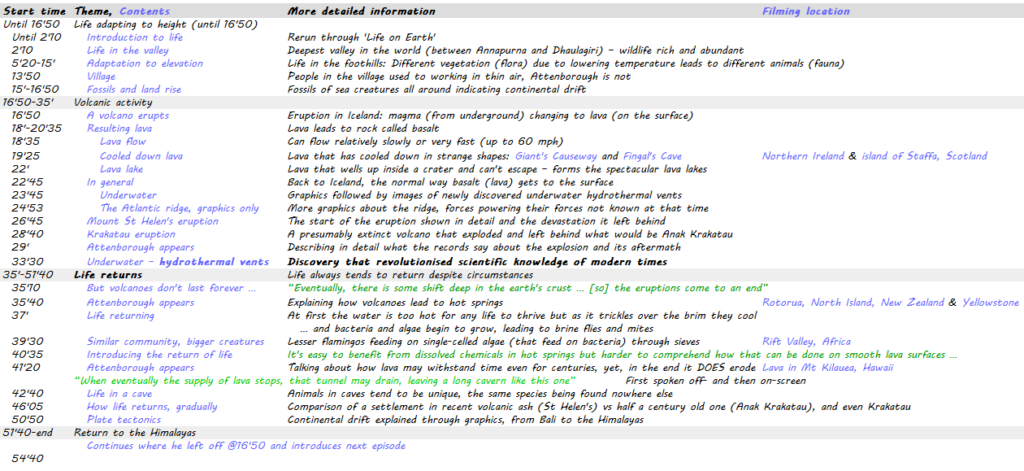

Scientific breakthrough – hydrothermal vents

Image on the left shows a hydrothermal vent (at the bottom of the ocean) and on the right there are a few animals feeding on the bacteria that transform the chemical energy from the vent (35′-35’25).

These images are not so big because of their beauty, they are so because of their scientific importance: these are hydrothermal vents. Until they were discovered scientists were convinced all life depended on the sun’s rays near the surface of the planet. However, here we have life, too far below the surface of the oceans for any rays to penetrate and the area is thriving with life obviously quite independent of the sun. Chemical energy derives from inside the earth and is taken up by bacteria that animals consume through their skin. These were actually discovered during the production of the “Life on Earth” series as pointed out in second part of Attenborough’s mini series “60 years …”, ten minutes into it (see timeline).

It is also interesting to note the story behind the eruption sequence. When preparing for the series the team decided they had to have some volcanic activity at the start of it. Below is a summary of his description of the happenings.

Plate tectonics (26’45-26’46)

The snapshots show how the “footage” switches from graphics to video. The switching from graphical presentation of the tectonic plates to actual recording of St Helens blowing its top off (image below).

Life in a cave (44’15-44’35)

Living organisms move in to cave systems as soon as possible. The frame on the left shows a tiny root (encircled) penetrading from the ceiling. This root belongs to a tree growing on the surface and the roots found their way through cracks in the rocks. On the right a more complex root system is growing, ideal for millipedes and other vegetarians. This obviously leads to there being centipedes and other carnivores (feeding on the plant eaters) and scavengers.

Because the animals in these cave systems are in total darkness they tend to lose their pigment (44’40-45′) as well as their eyes and wings (left) and rather feel their way around using long legs (right).

Life recovering from an eruption (46’25-48′)

Comparison of the state of life some two years after the eruption in St Helen’s, 1980 (top images), and an old one (bottom images). Top right image shows Attenborough picking up a seed of willow herb from a crevice, having presumably been blown from the nearby valley. Bottom left shows the state of development 57 years after the eruption of Anak Krakatau. On the right, Krakatau itself, a century after its eruption, having very lush vegetation. Reports state that there was nothing but deep sterile ash.

More recently (2019) the vegetation near St Helen’s has changed.

Introducing next episode

He ends this final piece of the programme turning around and looking at the peak of the neighbouring mountain as if this was the mountain where next programme would start.

“…Mountain ranges have been created in this way several times. The Himalaya are just the most recent. As they are worn down, they create different environments in which animals and plants can live. So we have begun our portrait of the planet up on the roof of the world, and we will go from high altitudes to low, from the poles to the equator. And in the next programme we’ll go even higher, to the most inhospitable environment of all, the world of snow and ice.”

Far from it. He is actually referring to the frozen environment, not this exact peak.

References

David Attenborough (2002) Life on Air, Memoir of a Broadcaster. BBC books. Pages, 299-301, 308-9.