A retrospective look at the Life Collection box as a whole

The collection contains (according to my definition) 8 series.

Many people love statistics. They reveal various interesting oddities, included here only for fun.

| Title | # of episodes | Total length (hrs, minutes’seconds) | Average length |

| Life on Earth | 13 | 11 hrs 11’04 | 53’846 sec |

| Living Planet | 12 | 10 hrs 32’30 | 54’33 |

| Trials | 12 | 9 hrs 47’25 | 48’30 |

| Plants | 06 | 4 hrs 53’47 | 49′ |

| Birds | 10 | 8 hrs 17’11 | 49’43 |

| Mammals | 10 | 8 hrs 21’46 | 50’10 |

| Undergrowth | 05 | 4 hrs 8’06 | 49’30 |

| Cold Blood* | 05 | 4 hrs 0’36 ——> 4 hrs 48’50 | 48’07 -> 57’30 |

It is interesting that although Life on Earth is obviously the longest series (the only one ever to include 13 episodes) on average Living Planet is longer. The single longest episode is the final one from Mammals series (58’49) being the only one surpassing the Living Planet’s episode about coastal life.

If the final episodes of the Birds and Mammals series (both dealing with conservation) were left out, being the only ones surpassing the 50 minute ‘barrier’ the Birds series would be longer than the mammals one.

* When Cold Blood series was produced BBC had started adding approximately ten minutes of “Behind the scenes” segment after each episode. This obviously makes them much longer and statistics more complex. Average and total length is given for both.

To appear or not to appear

At the start of Life on Earth it was decided that Attenborough should appear fairly regularly in each programme. This meant several obstacles to overcome including two episodes about insects (the miniature world) and one with fish (filming Attenborough underwater was challenging) and a single one about birds (they fly). Obviously mammals too would pose problems, being mainly active at night, but these could be overcome rather easily. More advanced technology in decades to come would help even more.

The first episode with insects (and other miniature animals like millipedes) was solved by rewriting the scripts so that Attenborough would appear only when talking about plants.

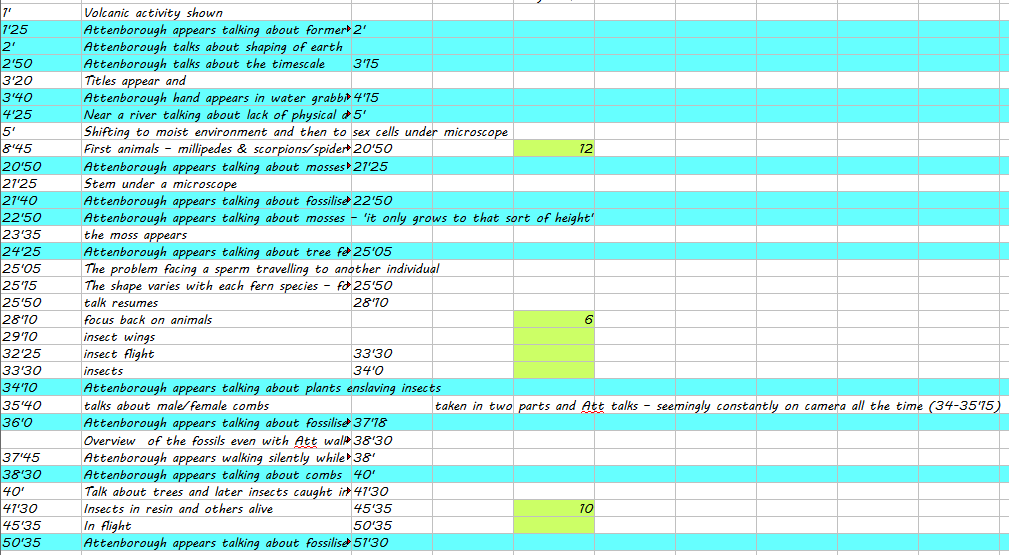

The table above shows when Attenborough shows up (blue) and when animals are on screen (green). Relatively similar lengths of time but never coincide.

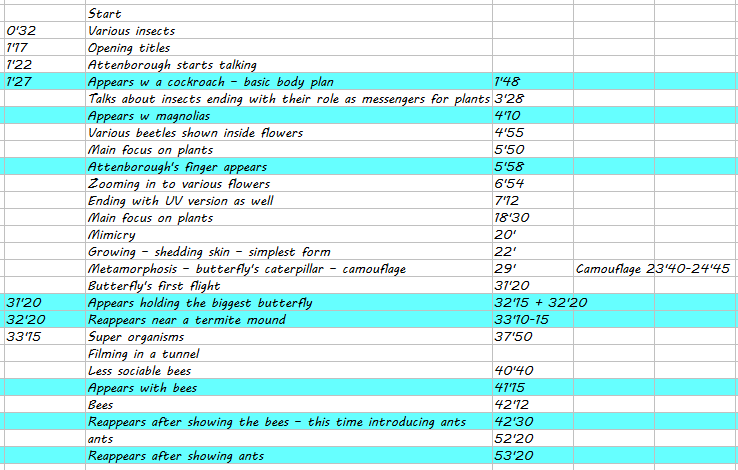

Similarly in the next episode (solely about insects) the whole script has to be written so that the size difference would not be too enormous. First time he appears he holds a cockroach (a reasonably big insect) in his hand, explaining the basic body plan.

As the table shows Attenborough only appeared when there would be minimal ‘conflict in sizes’. Rather appear with the biggest butterfly rather than a normal housefly.

Splitting the Life Collection

The first part (first 3 series) of the Life Collection has usually been regarded as a separate entity – a trilogy which plays a significant role in almost all their forthcoming ‘blue-chip’ series (the rest of the Collection and the “BBC Blockbusters” by using the theories and structures of those series. The first one deals with wildlife and its evolution, the next covers environments and ecology. The last has to do with animal behaviour. The rest of the collection (my definition of it) was published as a separate box set as Life on Land – along with “The First Eden”. Ironically they ignored “Life in the Freezer” just like I have preferred to. It may seem a bit strange to have the Birds and Mammals series included because both have a portion dealing with water. To BBC that has seemed irrelevant and I would agree.

The main reason for ignoring the “Life in the Freezer” as a part of the collection are given in the Writings part about the books in general.

The Trials of being a

The theories mentioned above are used repeatedly in the rest of the collection as well as in the following “Blockbusters”. Same applies to their structure: The “Plants” and “Birds” series seem very much like fitting into a pattern set by the “Trials” series. The “Mammals“, “Undergrowth“, and “Cold Blood” series are very zoological in their approach although Attenborough manages to sneak through the classification by making people feel it is more behavioural. Using the teeth and other ways of living is actually the way zoologists classify mammals as herbivores (plant eaters) and so on. The same obviously applies to Cold Blood, lumping snakes together and having them apart from crocodiles and lizards. It is similar with the Undergrowth series, but the categories are so enormous, all remaining invertebrates including scorpions, spiders and insects.

The final words

Attenborough series are well known for his tendency to end each episode/ programme with an introduction to the following one. This seems quite strange considering that in most cases he doesn’t do that. In only two series, “Living Planet” and “Birds” series does he regularly do this.

In most series there is a mixture of this tendency of introducing the next episode and having no reference to it, concentrating on the current subject.

In other cases he ends by praising the subject of that particular episode. At the end of the “Trials” episode about “Home Making” he talks about the termite mound :

“We might like to think that we are the most accomplished architects in the world, but if this was built in human terms with every worker termite the size of me, then it would stand a mile high. And we haven’t done that yet!”

As in every case when using his own words, they are taken straight from the subtitles file included with the digital version. Minimum fuss. Should also minimize the risk of errors.

Staying with the “Trials” series the final words of the first episode introduce the next one and so do the final words to the second one. After that there is hardly any such introductory words in any of the remaining episodes until, ironically, the final episode:

“This albatross is over 30 years old. She’s already a grandmother, and this year, once again, she’s produced a chick. She’ll devote the next ten months of her life looking after it. She has faced the trials of life and triumphed. For her little two-day-old chick, the trials are just beginning.”

Here he is simply pointing out the obvious fact that life goes on for the next generation.